Equity in Schools

Educating for Equity

Education for equity allows us to remove the predictability of student success based on any social or cultural characteristic, to interrupt practices that reproduce unjust access to opportunities, and to base learning on the talents and interests that each student and family brings to school.

Leading for Equity

Equity-centered leadership is establishing the conditions for each educator to engage in practices that lead to these outcomes. Equity-centered leaders engage educators in their schools to examine biases, commit to anti-racist practices, interrogate routines that reproduce inequality, and develop improvement strategies to transform teaching, learning and assessment.

CALL-ECL Equity Framework

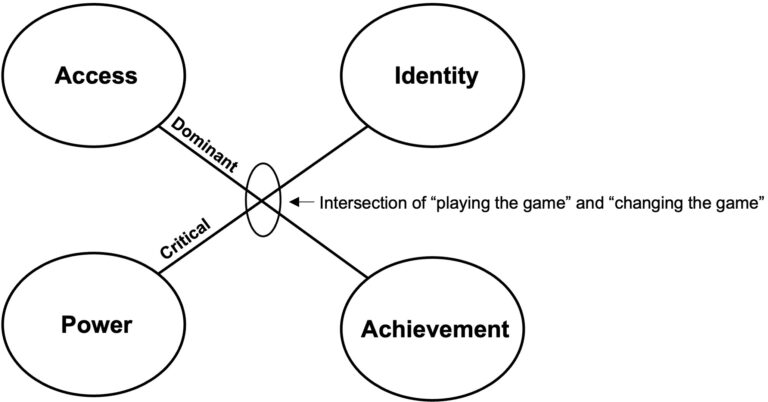

We use Rochelle Gutiérrez’ framework to describe two aspects of equity work: 1) practices to improve access to learning and achievement outcomes; and 2) practices that elicit the role of power in preserving inequality and the identity work that brings the voices and resources of students and communities into improvement efforts.

This framework will allow us to map how equity-centered leadership practices vary across district and school levels. This map will identify and share equity-centered leadership practices that will spark new learning for the ECPI partners, researchers, schools, communities.

Phases

- Research Questions

- How do districts develop and use networks to support principal development pipelines?

- How do districts design and implement equity-centered principal pipelines?

- What practices guide the work of equity-centered principals?

- Research Question

- How can we measure and support equity-centered school leadership practices?

- Research Question

- How can we design a process to measure the effects of equity-centered leadership preparation programs?

Equity Centered Leadership

School leaders establish the conditions for improving teaching, learning and community engagement for all families and learners. Equity-centered leaders focus specifically on creating high-quality learning environments that center the needs and interests of students and families who are not served well by existing systems. Equity-centered leadership has several dimensions:

First, equity-centered leaders improve access and achievement in existing school systems. Leaders engage in data-driven decision making to work with educators and communities to identify disparities in achievement outcomes, the application of disciplinary consequences, and the placement of students in programs such as special education. Equity-centered leaders clear away obstacles and create new pathways to include more students in rigorous learning and enrichment opportunities. They demonstrate an unwavering focus on the learning and wellbeing of students who have been historically underserved in schools, and support the professional growth of educators so that all students can succeed in the existing curriculum.

Second, equity centered leaders take a critical perspective on existing school systems. Equity-centered leaders reflect on their own biases and work to develop an asset-based mindset to build on the skills that educators, learners and families bring to school. They work with district and local leaders to identify structures and to disrupt routines that perpetuate bias and inequitable access to learning. They lead professional learning activities for educators to reflect on and correct deficit-centered practices and to model asset-based approaches. They shed light on family and community cultural wealth, celebrate and leverage accomplishments, and invite communities into conversations about school priorities and programs.

Third, equity-centered leaders collaboratively design equitable learning environments. They build organizational routines and a professional culture that value and celebrate the skills and knowledge that educators and learners bring. They work with educators to organize the design and implementation of engaging, culturally responsive curricula, behavioral supports, assessments and learning spaces. They obtain and distribute the resources necessary to support program design and professional learning. They systematically include the perspective of students, parents, extended family, allies/advocates in the design of environments that move beyond remediation toward joyful engagement for all learners.

ECL Resources

Research Design

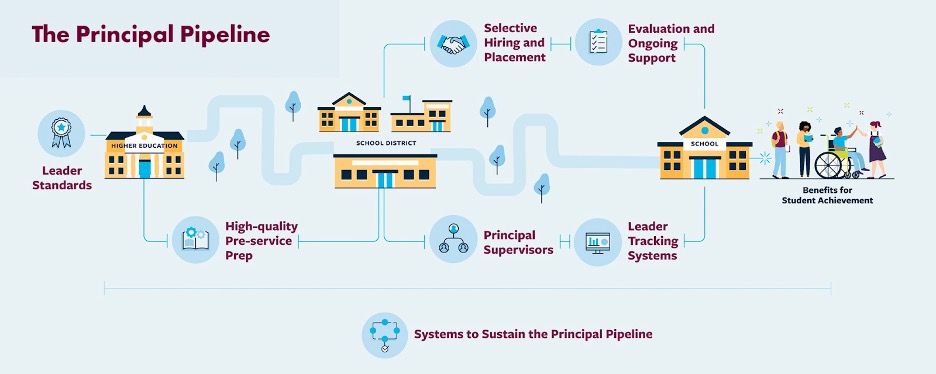

Recent research shows that comprehensive and aligned principal pipelines can make a very important difference for districts and schools. Implementation studies supported by the Wallace Foundation analyze in depth how school districts can strategically put in place policies, processes, and infrastructures to strengthen school leadership. Currently, the Wallace Foundation is supporting research that places equity in the center of principal pipeline development.

Learn more about the Wallace Foundation’s guide about leadership preparation.

CALL

The Comprehensive Assessment of Leadership for Learning survey (CALL) will serve as the model for the CALL-ECL survey. CALL is a system of surveys taken by all educators in a school and a district to measure school leadership management and improvement tasks. School leaders receive instant feedback through reports that document their school’s strengths and areas for improvement in the practices that matter to improve teaching and learning.

CALL domains are aligned with Professional Standards for Educational Leaders (PSEL) and include measures of leadership tasks that 1) focus school leadership efforts on instructional improvement; 2) provide data-driven support for teaching and learning; 3) develop professional communities among educators; 4) hire and support staff and acquire resources.

CALL has served over 750 schools in 200 districts in 30 states, as well as in Denmark, Japan, and Ecuador. More than 40,000 educators have participated in CALL. CALL researchers adapted the tool to measure and support leadership for teaching English language learners, remote teaching and learning, and personalized learning.

The research reported here was supported by the Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education, through Grant R305A090265 to the University of Wisconsin, Madison. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not represent views of the Institute or the U.S. Department of Education.